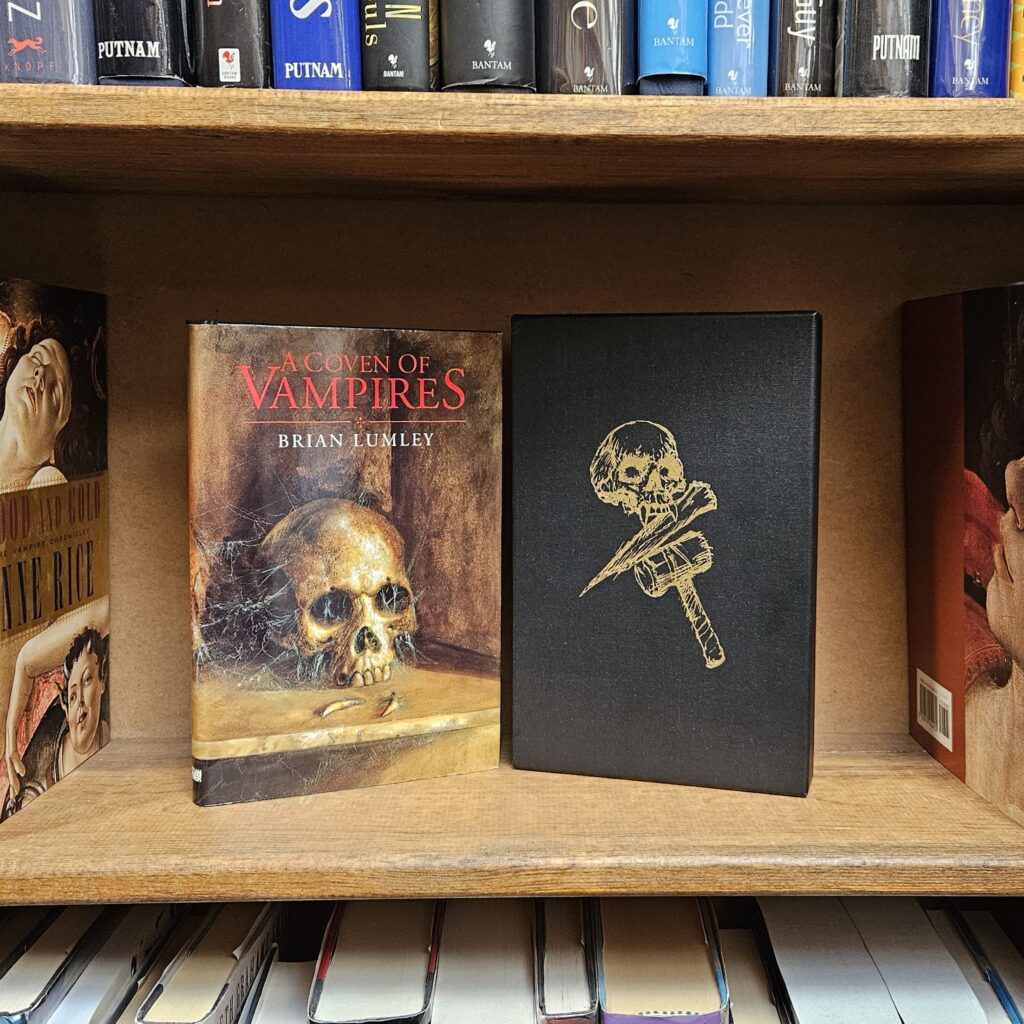

by Brian Lumley

SIGNED by Author and Illustrator | Limited Edition | Fedogan & Bremer | 1998

Brian Lumley (1937-2004) was an English horror author of the Lovecraftian tradition, having discovered the author as a teenager through a pastiche found in a British science fiction magazine–namely, Notebook Found in a Deserted House, by Robert Bloch–as well as becoming a avid collector of the author’s works while serving in the Corps of Royal Military Police as a young man.

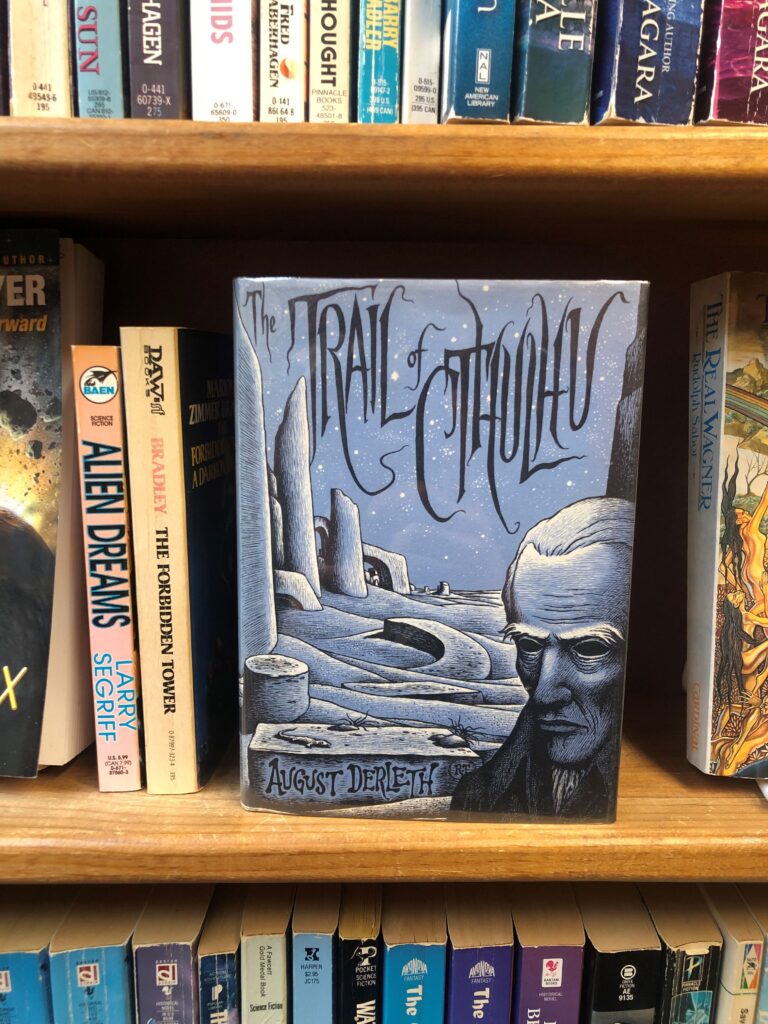

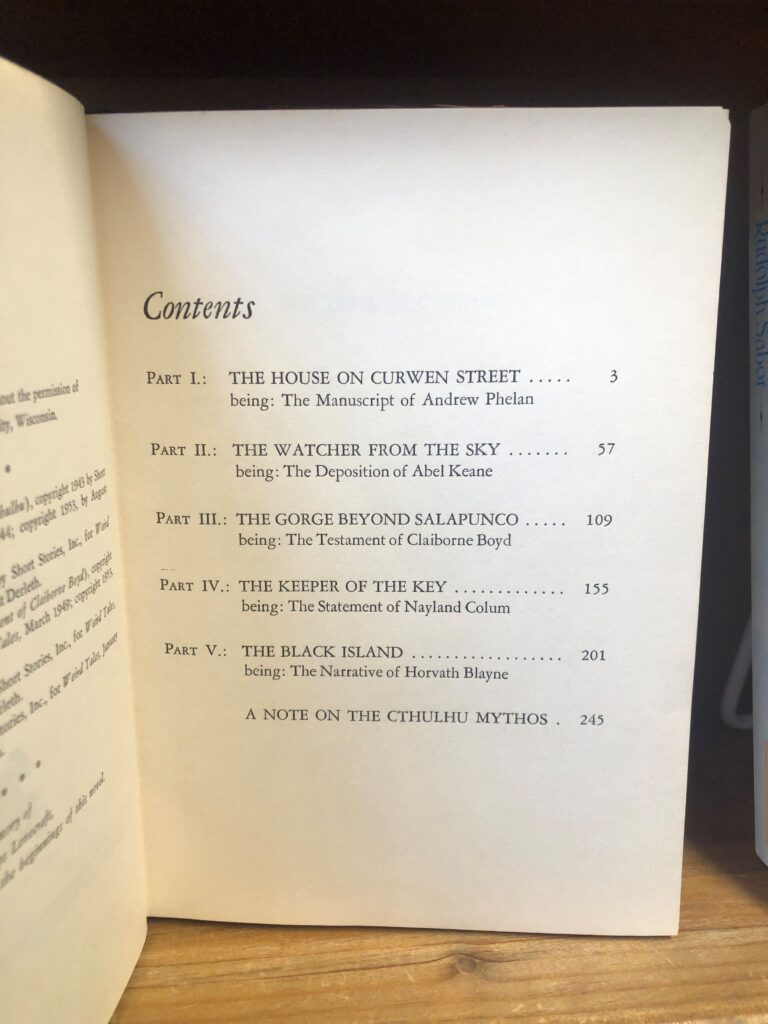

It was Lumley’s passion for collecting that eventually led to him becoming an author in his own right. In order to complete his collection, Lumley began corresponding with HP Lovecraft’s original publisher in America, Arkham House (named after the fictional New England town where Lovecraft set many of his stories). Lumley included some of his own Chthulu pastiches in his letters, and Arkham was so impressed with the young writer that he was invited to contribute some of his own writing to an upcoming anthology called Tales of the Chthulu Mythos. Thus began a forty year career steeped in the weird, the macabre, and, most notably, the Lovecraftian.

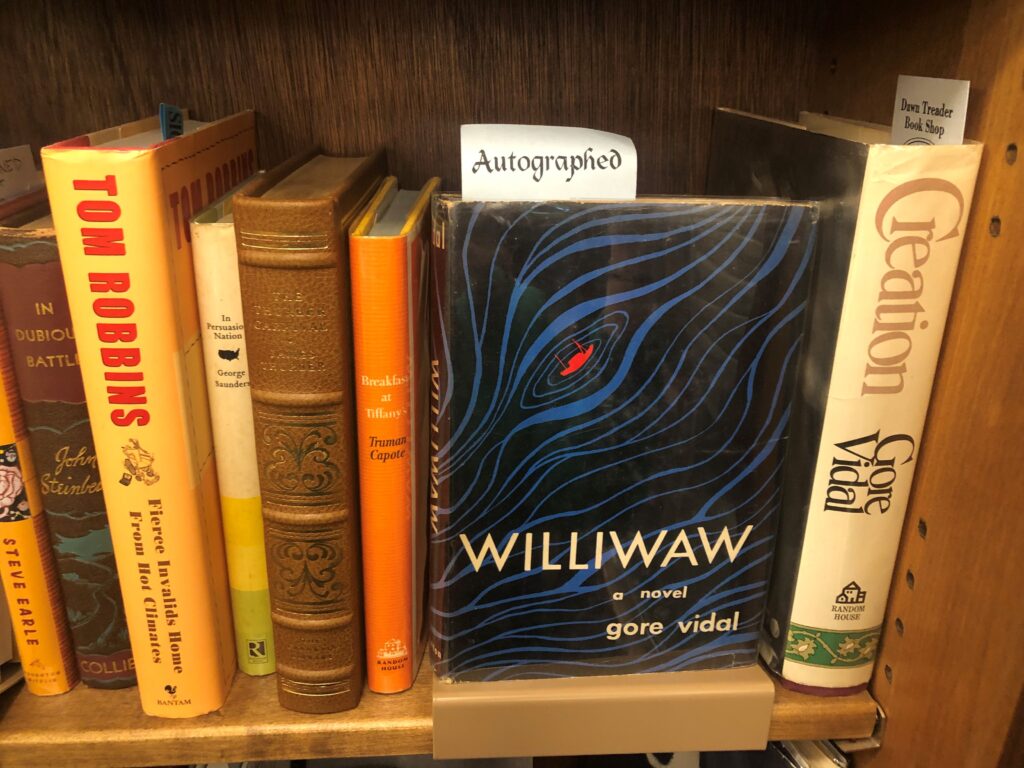

A Coven of Vampires, however, is a very unique collection of stories by an author best known for his work within, and adding to, the Cthulhu mythos. Previously published in various sci-fi and horror anthologies, these stories were all gathered together in a beautiful hardcover by Fedogan & Bremer–a publishing house that worked closely with Arkham over the years and that specialized in weird tales. A perfect fit for any of Lumley’s works.

This limited edition book is beautifully designed with a black and gold slipcase featuring a skull, stake, and hammer. The endpapers are blood red with a repeating bat design in black, while the interior is illustrated by the nine-time Hugo award winner Bob Eggleton. Signed by both Lumley and Eggleton, it’s the perfect collector’s item for anyone who loves Dracula, Carmilla, Lestat, Buffy, or truly any vampire stories modern or historic. And perhaps the start of your own career as writer, finding inspiration in the most unlikely of places.